If you’ve ever wondered why people poured so much money into websites that delivered dog food or how an online toy store became Wall Street’s darling, you’re in the right place. This guide will dissect the dot-com bubble in all its glory. We’ll delve deep into the factors that led up to this digital frenzy, the profound effects it had on the economy and investors, and the indelible legacy it left behind.

Best Crypto Exchange for Intermediate Traders and Investors

30+ million UserseToro is a multi-asset investment platform. The value of your investments may go up or down. Your capital is at risk. Don’t invest unless you’re prepared to lose all the money you invest. This is a high-risk investment and you should not expect to be protected if something goes wrong. Take 2 mins to learn more.

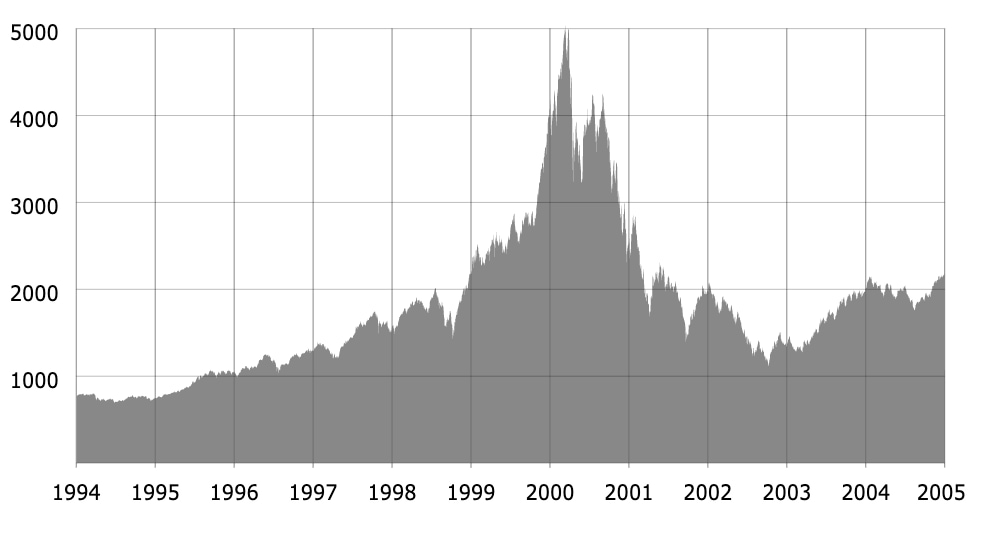

The dot-com bubble was a stock market bubble fueled by highly speculative investments in internet-based businesses during the bull market from 1995 to 2000. It saw the value of equity markets grow dramatically, with the technology-dominated Nasdaq index rising five-fold during that period.

Unfortunately, things started to change in the late 2000s once investors realized many of these companies had business models that weren’t viable, ushering in a bear market that would last around two years and affect the entire stock market.

The crash saw the Nasdaq index plunge 76.81%, from a peak of 5,048.62 on March 10, 2000, to 1,139.90 on October 4, 2002, culminating in the majority of dot-com stocks going bust and evaporating trillions of dollars of investment capital in its wake. It would take 15 years for the Nasdaq to retrieve its peak, which it did on April 24, 2015.

Recommended video: The dot-com bubble explained in 3 minutes

The internet changed everything…except basic stock valuation math. That, however, was not the general consensus during the latter part of the 1990s when stocks (especially tech stocks) increased in value at astounding rates – forming a bubble that market realities would eventually burst in dramatic fashion.

Beginner’s corner:

The dot-com bubble is an example of an asset bubble, sometimes referred to as a financial, economic, or speculative bubble. Noteworthy examples from history include the stock market bubble of the 1920s that led up to the Great Depression and the real estate bubble of the 2000s.

An asset bubble occurs when an asset’s price rises rapidly over a short period and trades much higher than its fundamentals suggest. Asset bubbles are fueled by increased money supply and particular historical circumstances (e.g., rapid technological expansion). The hallmark of a bubble is irrational exuberance*— the unfounded economic optimism that sees investors flock around a particular asset class without good reason.

During a bubble, investors bid up the price of an asset beyond its intrinsic value. Like a snowball, the bubble feeds on itself. The higher the prices, the more opportunistic investors jump in—the expectation of future price appreciation inviting in additional dollars, inflating the price even further.

Eventually, once prices crash and demand falls, the bubble pops, wreaking havoc for latecomers to the game, most of whom lose a large percentage of their investments. The burst has dire outcomes, such as reduced business and household spending and a potential economic decline (recession).

Asset bubbles are notoriously hard to recognize while occurring and are often identified only in retrospect.

*The term irrational exuberance was coined in December 1996 by Federal Reserve Board chairman Alan Greenspan and widely interpreted as a warning that the stock market might be overvalued.

Recommended video: What causes economic bubbles?

The 90s witnessed rapid technological progress in many areas across the U.S. However, the commercialization of the Internet led to the most remarkable expansion of capital growth in the country ever, seeing many investors eager to invest, at any valuation, in any dot-com company, especially if it had a “.com” after its name.

Ultimately, this grew into what’s now known as the dot-com bubble (aka dot-com boom, tech bubble, Internet bubble), triggered by a combination of speculative investing, market overconfidence, a surplus of venture capital funding, and the failure of Internet startups to turn a profit. It saw both venture capitalists and individual investors pour money into Internet-based companies, hoping they would one day become profitable, abandoning all caution for an opportunity to capitalize on the growing dot-com novelty vision.

Many investors expected Internet-based companies to succeed merely because the Internet was an innovation, even though the price of tech stocks soared far past their intrinsic value, increasing much faster than their counterparts in the real sector. As a result, investors anxious to find the next big dot-com were more than willing to overlook fundamental company analysis involving metrics such as price-earnings (P/E) ratio and base confidence on technological advancements.

For example, companies that had yet to generate any revenue, or profits, had no proprietary technology, and, in many instances, no finished product went to market with IPOs (Initial Public Offering) that witnessed their stock prices triple and quadruple in a day, leading to market-wide over-valuation of Internet firms. These outrageous valuations resulted in overwhelming demand, paving the way toward the inevitable burst of the bubble.

The overvalued and highly speculative startups eventually culminated in a stock market surge in 1995. Correspondingly, 1997 saw record amounts of capital flow into the Nasdaq, leading up to 39% of all venture capital investments going to Internet companies by 1999. That year, most of the 457 IPOs were related to Internet companies, followed by 91 in the first quarter of 2000 alone. As a result, between 1995 and 2000, the Nasdaq Composite stock market index rose 400%.

The eventual crash of the dot-com bubble can be attributed to the following factors:

One massive contributor to the dot-com bubble was investors’ lack of due diligence. Due to soaring demand and a lack of solid valuation models, most internet companies that held IPOs during the dot-com era were excessively overvalued. In short, companies were valued on earnings and profits that would not occur for several years, assuming that the business model actually worked, and investors were inclined to ignore traditional fundamentals.

As a result, investments in these high-tech companies were highly speculative, without solid profitability indicators rooted in data and logic, such as P/E ratios. Undoubtedly, this shortsighted investing strategy– resulting in unrealistic values that were too optimistic– blinded investors from the warning signs that ultimately signaled the bubble’s rupture.

With venture capitalists throwing money at the sector, dot-coms were racing to get big quickly, often spending a small fortune on marketing to establish brands that would distinguish them from the competition, with some throwing as much as 90% of their budget on advertising.

As a result, most Internet companies incurred net operating losses as they spent lavishly on advertising and promotions to build market share (percentage of a market/industry controlled by the company) or mind share (consumer awareness or popularity surrounding the company) as fast as possible. In addition, frequently, these companies would offer their services or products for free or at a discount to create enough brand awareness to charge profitable rates in the future.

Moreover, tech companies at the time were known for throwing expensive events called dot-com parties to generate buzz upon a launch (or any other reason for celebration, really). Budgets of up to a million dollars a month would sponsor extravagant parties in the Bay area, turning networking events into PR machines.

Indeed, the parties were often not more than pure exuberance facilitated by cheap money, rarely benefitting the company’s bottom line. This mindset was accurately concluded by Declan Fox, director of business development for Sony Music: “No one cares who threw the party, as long as it’s an open bar.”

The venture-funded dot-coms of the 90s that operated at a loss can be equated with today’s tech startups like food delivery and ride services (e.g., DoorDash, Uber). Similar to dot-coms, their goal is first to establish a dominant market position, at which point they can increase prices to a level where they will be profitable. However, by the same token, as these startups’ valuations surge, they are still not making any money.

We recommend you read Ranjan Roy’s article about DoorDash and “pizza arbitrage” as he compellingly demonstrates the failing business models of today’s delivery platforms: A pizza restaurant owner sees that DoorDash is selling his $24 pizzas for only $16, presenting him with an arbitrage (the simultaneous purchase and sale of the same product in different markets to profit from the difference in the listed price) opportunity: Order his pizzas at $16, sell them to DoorDash for $24 each, and pocket the difference.

Money pouring into dot-coms by venture capitalists and other investors was a primary reason for the bubble. Moreover, cheap money available through very low-interest rates made capital easily accessible. Furthermore, the Taxpayer Relief Act of 1997 lowered the top marginal capital gains tax in the U.S. and made people even more willing to make speculative investments.

That, coupled with fewer barriers to funding for tech and internet startups, led to massive investment in the sector, expanding the bubble even further.

Media companies encouraged the public to invest in risky tech stocks by peddling overly optimistic expectations of future returns. Similarly, business publications – such as The Wall Street Journal, Forbes, Bloomberg, as well as many investment analysis publications – stimulated demand even further, taking advantage of the public’s desire to invest in the stock market.

The Nasdaq index peaked at 5048 on March 10, 2000, nearly doubling from the previous year. After the peak, several leading high-tech companies, such as Dell and Cisco (NASDAQ: CSCO), placed colossal sell orders, sparking panic selling among investors, resulting in the value of many tech companies nosediving. Within weeks, the stock market had lost 10% of its value.

The downturn was further intensified by:

Ultimately, these factors helped catalyze the bursting of the overinflated Internet bubble. As cash-strapped Internet companies began to lose value, spreading fear among investors and causing additional selling, a self-reinforcing process called capitulation (a mass surrender to the declining market) took hold. As a result, dot-com companies that reached market capitalizations in the hundreds of millions of dollars became worthless within months.

The sell-off continued until the Nasdaq hit its bottom around October 2002, dropping to 1,114, down 78% from its peak. By 2001, a bulk of publicly traded dot-com companies had folded, with trillions (estimated $5 trillion) of dollars of investment capital evaporated.

It took until 2008 for high-tech industries to exceed unemployment levels before the recession, increasing 4% from 2001 to 2008. The tech industry in Silicon Valley took longer to recover, with some companies having to relocate production phases to lower-cost areas.

After venture capital dried up, so did the start-ups they funded. The lifespan of a dot-com was directly correlated to its burn rate, the rate at which it was burning through its capital—resulting in many dot-com companies going into liquidation. Moreover, supporting industries, such as advertising and shipping, scaled back their operations as demand fell.

Multiple Internet companies and their executives were accused (or convicted) of fraud for misusing shareholders’ money. In addition, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) imposed hefty fines against investment firms, including Citigroup (NYSE: C) and Merrill Lynch, for deceiving investors.

However, a select few– through reorganization, new leadership, and redefined business plans– managed to adapt and thus survive the burst. Some companies that managed to do just that include Amazon (NASDAQ: AMZN), eBay (NASDAQ: EBAY), Priceline, and Shutterfly.

Contrary to public opinion (that most dot-com companies failed), according to David Kirsch, director of the Dot Com Archive, 48% of dot-com businesses were still around in late 2004 (though at lower valuations). He adds that the dot-com survival rate is as good as or better than that for other technologies (e.g., automobiles, TVs) in their formative years.

The company that most exemplified the dot-com era was Priceline. Launching in 1998, Priceline was founded by Jay Walker and intended to solve the problem of unsold airline seats. Priceline’s fix was to offer these seats to online customers who could name the price they were willing to pay.

As a result, customers got cheaper flights, and airlines sold excess inventory. In short, inefficiencies were ironed out of the market, and Priceline took a cut for streamlining the process.

The company was a dot-com sensation, expanding from 50 employees to more than 300 and selling an excess of 100,000 airline tickets in its first seven months of business. By 1999, it was selling more than 1,000 tickets a day.

Walker wanted to saturate the market by building a brand through rigorous marketing. So the company spent more than $20 million in advertising in its first six months, eventually placing fifth in internet brand awareness by 1998, preceded only by AOL, Yahoo, Netscape, and Amazon.

And so, in March 1999, Priceline went public at $16 a share, eventually settling at $69, giving it a market capitalization of $9.8 billion, the most significant first-day valuation of an internet company to that date.

At the same time, Priceline had racked up losses of $142.5 million in its first few quarters in business. In addition, it bought tickets on the open market to fulfill customers’ bids, thus losing approximately $30 on every ticket it sold. Furthermore, Priceline customers frequently paid more at an auction than they could have through a traditional travel agent.

None of this fazed investors, however, because they were more interested in grabbing a slice of the buzz. It didn’t matter for venture capitalists either, whose goal in backing companies like Priceline, eToys, and Kozmo.com, was outlandish IPOs, since that’s when they got paid.

Best Crypto Exchange for Intermediate Traders and Investors